Exponential Wealth Creation and Investor Self-Sabotage

Investor Expectations of Retailers Heading Into Black Friday. Nov 27, 2013. AlphaNow, Thomson Reuters.

MarketPsych Unveils New Predictive Analytic Tools. Nov 14, 2013. Faye Kilburn. Inside Market Data.

Trader's Tap Twitter for Top Stock Tweets. Oct 11, 2013. James Macintosh. Financial Times.

Curtain Could Fall on Social Media ETF Party Oct 8, 2013. Trang Ho. Investor's Business Daily.

Upcoming Events

MarketPsych's Chief Data Scientist and Visionary - Aleksander Fafula - and Richard Peterson are in London this week and Dr. Peterson will be speaking in Boston on December 12, 2013.

OPTIONALITY AND WEALTH CREATION

Optionality is the property of asymmetric upside (preferably unlimited) with correspondingly limited downside (preferably tiny).

~ Nassim Taleb, Antifragile

Most investors have a story of "the one that got away" - a good investments that would have made them a fortune, but alas... Such investments usually possesed the property of optionality, so that the missed return is often several times the initial investment. Like most, I've had a few big misses. For one the President of Dell Computer taught an undergraduate class of mine in Austin, Texas in 1992 and repeatedly told me, "if you want to get rich, buy Dell stock and hold on," but alas the stock's P/E ratio was too high for my valuation models and I was a dogmatic value investor, and alas ... (Dell stock was up 100x over the next 6 years). Even worse, I initially dismissed the internet. I had dinner with my college electrical engineering professors who explained the internet would change everything (this was 1994). At the time I reflected on the painfully slow Mosaic browser and the limited availability of web content, and I vocally disagreed (the memory of my limited vision still hurts). I remember these events because the professors outlined their visions with such wonder. The professors were truly in awe of the world's upcoming transformations.If you 'have optionality’, you don't have much need for what is commonly called intelligence, knowledge, insight, skills, and these complicated things that take place in our brain cells. For you don't have to be right that often. All you need is the wisdom to not do unintelligent things to hurt yourself (some acts of omission) and recognize favorable outcomes when they occur.

~ Nassim Taleb, Antifragile

I learned a few things from these missed opportunities. Each opportunity had enormous - life changing - upside and limited downside. To take advantage of such optionality, we've got to first look for this property. We need the long-term vision to see over the horizon at the exponential changes coming our way. Moreover, we need both the aggressiveness to act on our vision and the prudence to avoid sabotaging ourselves as we pursue it.

Optionality is on my mind lately as Bitcoin and alternative cryptocurrencies (Litecoin, Feathercoin, etc...) continue their ascendance. We described the cryptocurrency bubble in March in this newsletter. In that newsletter you can see a chart of bitcoin as it was about to hit $100 per bitcoin. Today bitcoin is over $1,000 per bitcoin, driven in part by explicit acceptance of virtual currencies by the SEC and Federal Reserve and new Chinese exchanges catering to tech-savvy Chinese moving their savings offshore. Many courageous investors have gained paper (and real) wealth by speculating on cryptocurrencies early, and so today I thought it pertinent to look at the fundamental drivers of wealth accumulation, which is, after all, why we invest.

Today's newsletter explores the creation of massive wealth and the mental biases that sabotage its pursuit.

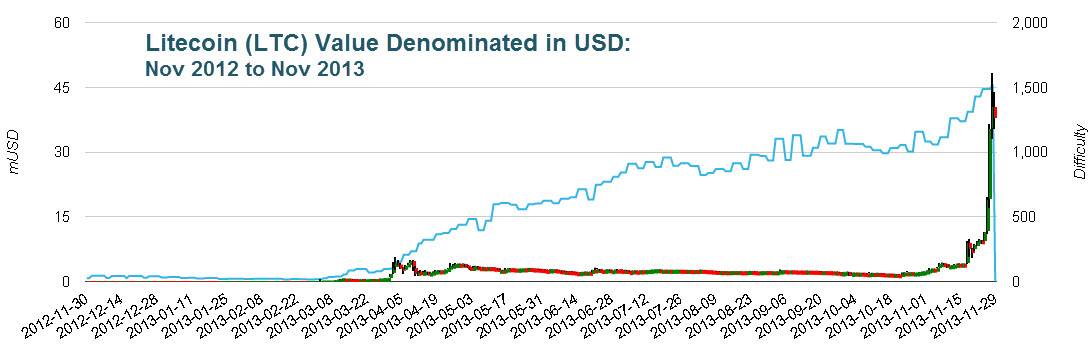

VIRTUALLY EXPONENTIAL

While Bitcoin has been in the headlines for rising over 5,000+% this year, other coins have had even more spectacular gains. In February 2013 - 10 months ago - Litecoin (LTC) was trading on online exchanges like BTC-e.com for $0.05 per coin. However this was an illiquid market - if you tried to buy LTC you would find that an investment of $10,000 in one hour would at least double the price. So finesse was required to buy any. LTC was one of a dozen alternative coins, many of which were "pre-mined" by their originators and were located on offshore exchanges where hacked or frozen user accounts and security breaches (and lost coins) was commonplace. And that's exactly why most people left LTC alone - information was sparse (but could could be obtained by trawling djargon-laden eveloper sites and chat rooms), and the exchanges where it could be traded were both unstable and opaque. On Thursday last week LTC hit $50 per coin, for an appreciation of 100,000% in 9 months (1000x). See an interesting 12-month price chart of LTC below:

Yet this appreciation was not entirely unpredictable. In our latest currency research on our Thomson Reuters MarketPsych Indices, which you can see written up in this new whitepaper by Ian McGillvray (now at Google), the MarketPsych country-level FinancialSystemInstability index, is a positive predictor of a currency's future value on a monthly basis. That financial system instability in a country in one month is positively predictive of the country's currency value one month later may seem counterintuitive, but this finding goes along with the volumes of literature on the benefits of contrarian investing. A video introduction to the white paper is viewable here.

BENJAMIN GRAHAM HITS A HOME RUN

Value investing is a subtype of contrarian investing, and Benjamin Graham is widely regarded as the modern father of value investing. Warren Buffett is the most recognizable of Graham's many successful acolytes. First editions of Graham's book "The Intelligent Investor" are revered at some funds as a book of Universal Truth, while his aphorisms are passed out to trainees as investing (and life) lessons.Despite being the scholar behind value investing, Graham himself had unspectacular investment performance except for one specific investment - GEICO. Per Graham (1976), "In 1948, we made our GEICO investment and from then on, we seemed to be very brilliant people." GEICO accounted for more profits to his Graham-Newmann investment partnership than all of his other investments combined.

Like the Dell investment I avoided during college because it was "overpriced" on a value basis, Graham initially declined to buy GEICO stock because its valuation exceeded his framework. With some difficulty, his investing partner Newmann persuaded Graham to make an exception to the rigorous valuation criteria encapsulated in his model. Read more about the GEICO, Graham, and Buffett story here.

It's not only Ben Graham who became wealthy on the back of one key investment that captured enormous upside. Consider the world's billionaires, nearly all of whom are wealthy due to one very successful business (Bill Gates, the Google guys, Mark Zuckerberg, etc...). But aside from business owners, many wealthy investors such as Warren Buffett and Carlos Slim - who identify and invest in others' excellent businesses - have made 3 or 4 fantastic investments that generated the vast bulk of their outperformance. Enormous wealth is often generated in a fashion described by Mark Twain and repeated by Andrew Carnegie (a U.S. Steel baron) in his essay "How to Succeed in Life:" Put all your eggs in the one basket and --- WATCH THAT BASKET.

Managing a diversified portfolio can help investors grow their wealth gradually over time. Yet most extremely wealthy individuals became wealthy because they did not diversify. This is dangerous to say, since it contradicts financial advisory doctrine which is intended to protect us from our own bad ideas (putting all our money into our cousin's leveraged Alberta gold mine, for example). Yet with proper judgment and limiting the amount of capital invested in long-shots, it can be a very impressive strategy. For example, one of the best long-term investors I know keeps 80% of his assets in cash-equivalents and takes massive focused risks with the remaining 20% (with that 20% distributed over several independent positions). Yet limiting risky investments to 20% of one's assets is difficult for most to do.

Most investors make crucial mistakes when watching just "one basket." Sometimes their attention is captured and shifted by the media, and they forget to tend the basket ("poor planning and neglect"). Sometimes the basket drops, the eggs crack, and rather than moving on, they focus even more attention on trying to salvage it in an ultimately losing situation ("holding losers too long"). More often, they simply sell their basket to the first and highest bidder, moving on to another basket, but never truly unlocking the true value in it ("cutting winners short"). In the next sections, I'll address each of these wealth-inhibiting mistakes.

CUTTING LOSERS

Ask yourself: Is it emotionally more difficult to buy into or to sell out of a investment?The vast majority of investors answer, to sell.

Now ask yourself: Which decision - to buy or to sell - consumes more of your time?

Most investors report spending 80% or more of their time on the buy decision.

This imbalance in time and energy spent on the buy decision versus the sell decision reflects two biases rooted in Daniel Kahneman's Prospect Theory and called "The Disposition Effect" by Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman. The disposition effect is more familiar to traders embodied in the sayings, "holding losers too long" and "cutting winners short."

One common characteristic I've encountered in successful fund managers is an intense aversion to losses. One very successful manager told me: "I have to take losses as quickly as possible, it relieves an uncomfortable tension in me." The successful managers can't stand the emotional pain and drain of holding losers. The ratio of average win size to average loss size among these top portfolio managers is up to 8 to 1. In the parlance of trading, they are very good at holding their winners and cutting their losers short.

Most investors do not watch the markets daily, and they don't want to think about managing losses actively. To solve for the fact that most of us are not professional investors, Benjamin Graham encouraged value investors to find investments with a large "margin of safety" - a discount to book value - in order to ensure that even if the company closed, they would be returned more than their initial investment after the conpany's assets were sold off. This margin of safety allows investors to feel confidence in their investment - and avoid panic selling - even as their investment value falls further. The margin of safety is not only intelligent for fundamental value reasons, but it is also a psychological tool that helps them avoid impulsively selling when the pain of losing finally becomes too intense.

HOLDING WINNERS

J.R. Simplot is an American eighth-grade dropout and a self-made multi-billionaire. He made his fortune through saavy investments in potato farming and french fry production. He owns the largest ranch in the United States, the ZX Ranch in southern Oregon. His ranch is larger than the state of Delaware. Despite his tremendous wealth, Simplot is a modest man. He describes his accumulation of wealth to Eric Schlosser in the book Fast Food Nation:According to some experts, selling winning positions too soon is a result of "seeking pride." Others believe that cutting winners short is driven by the fear that one might lose what one has recently earned ("I don't want to give it back"). Whatever the reason for it, selling winners short guarantees that good investments never become great. Note that even Warren Buffett has committed this error, selling out of his GEICO investment much too early, back in the 1960s. Subsequently his mentor Benjamin Graham continued to ride it higher."Hell, fellow, I'm just an old farmer got some luck," Simplot said, when I asked about the keys to his success. "The only thing I did smart, and just remember this ó ninety-nine percent of people would have sold out when they got their first twenty-five or thirty million. I didn't sell out. I just hung on."

One key to managing risk in investments with long-term optionality is to identify, "what is the crux of my vision, and what specific factors does the realization of that vision rely upon?" If the long-term fundamental conditions for that vision have not changed, then there is no reason to sell.

BUYING INTO INSTABILITY

One of the theories about the historical ourperformance of value investing strategies references investor risk perception. Value investors buy assets that are mispriced (undervalued) because others do not want them. Non-value investors perceive excessive risk. Pessimism about the future of an asset's price is presumed to be due to emotional factors (fear) that leads investors to over-estimate the odds of negative events. An investing style based on such an approach - of finding assets that are underpriced because others do not want them - is contrarian.We seek to buy from pessimists and sell to optimists.

~ Benjamin Graham

Trading genius (and fortunately for MarketPsych, our Chief of Analytics) Changjie Liu developed several contrarian investment strategies using our sentiment data based on the value-investment premise that the prices of assets at extremes of sentiment (extreme negative or extreme positive) tend to mean-revert over time. Changjie found strong evidence of the value of contrarian investing in global equities and U.S. equities in our sentiment data over 12 month holding periods. In global equities we see that buying equities in countries with high Government Instability is one of the most profitable tactics. This past newsletter describes the basics of our global strategy (note the since-confirmed buy signal on Pakistani equities). In U.S. equities we find that Anger (at a company, its management, or its customer relations) is the ideal contrarian sentiment - even more valuable than investor Fear. When Anger is high, investors throw the baby out with the bathwater. When Anger dissipates, stocks tend to rise sharply. Changjie's contrarian equities strategies have been updating live on our website since February. These strategies do not utilize fundamental or technical information but rely on sentiment data alone. Besides excellent in-sample results, his contrarian global equities and U.S. equities strategies have continued to perform very well in live forward-testing this year. Please contact us for more information.

Contrarian investing strategies allow us to gain extra leverage on investments with optionality. Too often, if a good idea is recognized, its potential quickly becomes priced in. By buying opportunities that others do not see or are averse to, the odds of capturing optionality increase.

TRADING CORNER

Each month we discuss investment ideas from Changjie's models as well as investment ideas based on our own sentiment-based indicators and trading models. We have an enormous array of models within our website. Our web specialist Nareg Khoshafian is happy to give potential users a free tour.Please sign up here for the Basic Plan to see our investment perspective and ideas as well as to gain access to our sentiment Dashboards and Top Lists. Professional website users receive access to many additional features including our new sentiment indicators for each assets and equity as well as our charting tools. Please contact us directly if you represent an institution.

HOUSEKEEPING AND CLOSING

Please contact us if you'd like to see into the mind of the market using our Thomson Reuters MarketPsych Indices to monitor market psychology and macroeconomic trends for 30 currencies, 50 commodities, 120 countries, 40 equity sectors and industries, and 5,000 individual equities extracted in real-time from millions of social and news media articles every day.[O]ne lucky break, or one supremely shrewd decision - can we tell them apart? - may count for more than a lifetime of journeyman efforts. But behind the luck, or the crucial decision, there must usually exist a background of preparation and disciplines capacity. One needs to be sufficiently established and recognized so that these opportunities will knock at his particular door. One must have the means, the judgment, and the courage to take advantage of them.

~ Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor (added to the 1971/1972 Edition).

We love to chat with our readers about their experience with psychology in the markets and with behavioral economics! Please also send us feedback on what you'd like to hear more about in this area.

Happy Investing!

Richard L. Peterson, M.D. and the MarketPsych Team